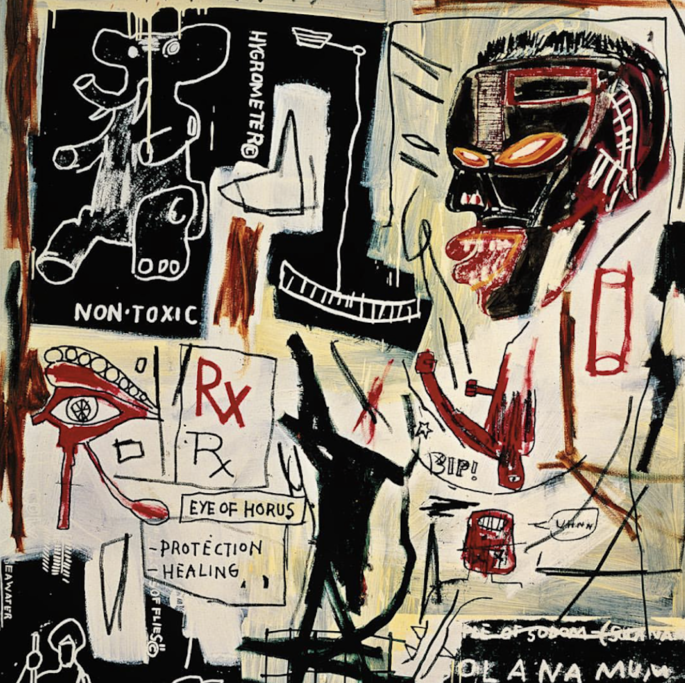

As he boarded a plane for Hong Kong in late 2016, Brett Gorvy, then global head of postwar and contemporary art at Christie’s, posted an image of a Jean-Michel Basquiat painting on his Instagram feed.

Upon landing, he found he had three text messages from clients interested in buying the 1982 work, a portrait of Sugar Ray Robinson and part of an upcoming private-sale exhibition. One client swiftly put the painting on hold and purchased it two days later, reportedly for about $24 million. Today, looking back, Gorvy claims it all happened by accident. His post, he explains, “wasn’t about marketing or selling. It was just like, I’ve got something really special, and I’d love the public to share it.” Despite his demurral, this sale—widely regarded as the first major blue-chip Instagram transaction—signalled the power the app had attained in the art world’s upper echelons, where not so long ago dealers staunchly maintained that no true collector would dream of buying from a jpeg.

Over the past eight years, Instagram has become an indispensable, all-purpose tool for everything art related.

Dealers increasingly report making sales to collectors whose interest has been piqued by seeing work on the app. For museums and galleries, it’s an essential, cost-effective way to build audiences and market shows. Emerging artists have used it to establish themselves and find collectors, and high-flying art-market stars are embracing it as well, in diverse ways.

‘Heavenly Bodies: Fashion and the Catholic Imagination’ exhibition at The Met Museum, via @metmuseum instagram

Art itself is such a beloved subject on Instagram that #art was the fifth most popular hashtag on the app last year. Yet Instagram’s universal popularity is not just a simple matter of sharing pictures. It’s also a case of thoughtful design—the obsession of the company’s founders, Kevin Systrom and Mike Krieger. “Kevin and I have a lot of interest in design and in art and in craft,” says Krieger, now the CTO and an avid art collector himself. When the pair launched Instagram in 2010, he says, “there were a lot of things we did under the hood,” like automatically applying a sharpening filter that made early iPhone photos look beautiful. The carefully researched filters drew on vintage photography, and the famous square format, which recalled medium-format cameras, “helped people crop before they understood the rule of thirds,” Krieger says.

There are a lot of people out there who like to be inspired. ’ —Brett Gorvy

The answer to Instagram’s popularity also lies partly in Krieger’s particular expertise. As well as being, in the words of a former classmate, a “stud engineer,” Krieger brought the app one of its secret ingredients: an understanding of persuasive technology, the study of how computing products are able to influence human behavior.

Image via @LACMA instagram

Krieger studied the field at Stanford University with one of its pioneering scholars, the behaviour scientist BJ Fogg, helping Fogg with a seminal 2007 paper titled “The Behavior Chain for Online Participation: How Successful Web Services Structure Persuasion.” In one of Fogg’s classes, anticipating the widespread use of smartphones, Krieger built a prototype for a program called Send the Sunshine, which would prompt people in bright latitudes to email pictures of the sun to friends in darker climes. (He and his sister had recently moved to the U.S. from Brazil, where they grew up, and she, studying in Chicago, craved light.) Fogg admired the Send the Sunshine concept from the start. “I loved how simple it was,” he recalls, noting that “the pattern of everything that has gone big is to start very simple and focused.” It was the same with Instagram, Fogg says: “Mikey and his team just kept it very, very simple and limited the functionality.” Systrom and Krieger were canny about marketing, tapping top web designers as beta testers. Also crucial was their early focus on building community.

Within months of instagram’s launch, San Francisco Instagram fans dreamed up the InstaMeet concept—basically, a group photo-taking excursion—and Krieger and Systrom often joined them. The company swiftly adopted the idea and took it global, posting strong photos with the #InstaMeet hashtag to company-controlled feeds.

By the time Facebook acquired Instagram for $1 billion in April 2012, it had designers beyond the tech world on board. Artists and photographers soon followed, and museums began building on the InstaMeet concept. New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art pioneered the Empty, an InstaMeet held during closing hours, in April 2013, and Instagram again nudged the idea along: Kristen Joy Watts, then the company’s New York-based community team leader for art and fashion, helped several other museums, fairs and galleries set up their own Empties.

Still, the art world’s embrace of Instagram has happened mostly organically, especially as compared with other sectors, or “verticals,” like lifestyle, beauty, entertainment and sports, which have internal support. Fashion, for instance, has a champion in former magazine editor Eva Chen, who handles the company’s fashion partnerships, while Watts now edits the new @design channel. The art world, by contrast, has no dedicated Instagram liaison.

Melting Point of Ice, 1984, and Pink Devil, 1984, by Jean-Michel Basquiat. Image via @thebroadmuseum instagram

Today, the Met ranks No. 2 on Instagram’s top geotagged museums list, behind the Louvre and ahead of New York’s Museum of Modern Art – a position it’s maintained since the company began keeping score three years ago. And now that the Empty concept is “mature,” as Kimberly Drew, the Met’s social-media manager, puts it, arts organizations have created endless variations. “There are just tons of different ways to cut the cake on it,” says Drew, an influencer herself: Her feed, @museummammy, has around 190,000 follow.

One phenomenon of the Instagram age is the FOMO-inducing selfie, the pursuit of which can lead to multiblock lines for particularly Instagrammable art installations or gallery shows. Celebrity posts have certainly contributed to this development. Katy Perry’s Instagram post of a Yayoi Kusama mirror room helped draw crowds to L.A.’s Broad museum soon after it opened, in 2015, and also inspired Adele to shoot a music video there.

But The Broad Museum has learned, through surveys, that almost a quarter of guests arrive there after seeing pictures on a friend’s social-media feed. People often pose in front of The Broad’s blue balloon dog by Jeff Koons, whose name alone has been hashtagged on the app more than 290,000 times. Joanne Heyler, the museum’s director, believes that visitors use Instagram the way earlier generations used gift-shop postcards. “This is a viral version of that,” she says.

At the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, two eye-catching installations—Chris Burden’s 2008 Urban Light, a stand of 202 cast-iron lampposts in front of the campus, and Michael Heizer’s 2012 Levitated Mass, the 340-ton megalith that hovers behind it—are the backdrop for so many selfies that LACMA is No. 4 on Instagram’s top geotagged museums list, despite having 57 percent fewer visitors than No. 3 MoMA. “In ancient times, monumental sculpture was a way to create a sense of place,” says Michael Govan, the museum’s director, adding that an Instagram post of a powerful artwork is “the most recent expression of an age-old idea of a sense of place and identity.”

Jeff Koons, Balloon Dog, 1994-2000. Mirror-polished stainless steel with transparent colour coating by Jeff Koons. Image via @thebroadmuseum instagram

For artists, Instagram has become a key to everything from establishing careers to finding collectors to making work. Last summer, LACMA turned over its feed for 12 weeks to L.A.-based artist Guadalupe Rosales, who maintains two Instagram archives of local Latino culture: @map_pointz (25,100 followers) covers the ’90s party scene, and @veteranas_and_rucas (163,000 followers) focuses on women. “She talked about her own interests,” says Govan, who discovered Rosales’s work at East L.A.’s Vincent Price Art Museum. “I was sad when it ended, because I was less interested in our own.”

Those who already have global reputations use the app to build their star power and summon their own crowds.

For a recent show at New York’s Galerie Perrotin, Takashi Murakami, who has roughly 683,000 Instagram followers, held a private InstaMeet preview—as a result, thousands of visitors came to the opening weekend. (Even so, Emmanuel Perrotin, Murakami’s dealer, notes that Instagram allows dealers to promote all artists equally, even those who don’t have massive followings.)

Photographer Stephen Shore, who has around 146,000 followers, finds Instagram a useful discipline, one that has come to dominate his oeuvre. He dedicated four years to making photos for the app, images he showed in his 2017–18 MoMA retrospective using iPads. He continues to post about once a day, always using Instagram’s original square frame. “I’m convinced it’s still probably best square,” Shore says, in part because of how it recalls the Polaroid SX-70, a camera popular in the 1970s among photographers who used it to take the same kind of “notational” picture he sees a lot of on Instagram today. He also values the community of like-minded people expressing themselves through visual imagery. “I’ve likened it to Enlightenment scholars,” he says, “one in Paris and one in Amsterdam, having a weekly correspondence, but never meeting.”

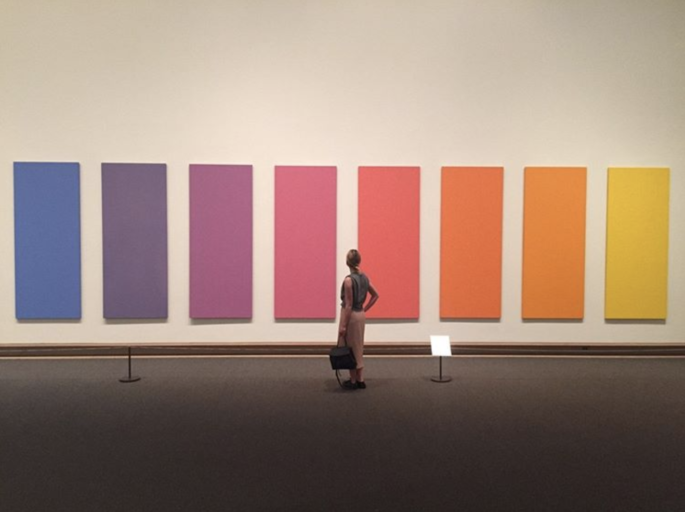

Ellsworth Kelly’s rainbow-colored “Spectrum V,” 1969. Image via @metmuseum instagram

Over the past five years, Instagram has evolved the app to encompass video, different layouts, portrait and landscape modes, the Snapchat-like Stories, Live, slideshows and IGTV, offering users, as head of design Ian Spalter says, “a wider palette of options for expression.”

Instagram is now so flexible that its uses seem as varied as art itself.

For Hans Ulrich Obrist, artistic director of London’s Serpentine Galleries, Instagram serves as a fantastic research tool. “It doesn’t really replace the experience of art,” he says. “But it’s a way of seeing shows that one just cannot get to physically.” Obrist fills his feed, which has around 223,000 followers, with handwritten notes and drawings by artist friends like Etel Adnan, Ryan Trecartin and Anri Sala. It’s become a curatorial project in itself, one he intends to publish as a book.

Constantin Brancusi. “Endless Column.” version I, 1918. Oak. Gift of Mary Sisler. © Succession Brancusi. Image via @themuseumofmodernart instagram

These days, Brett Gorvy, now a partner in the gallery Lévy Gorvy, is known for his eclectic, connoisseurial Instagram posts, which might juxtapose Albrecht Dürer self-portraits with some lines from Friedrich Nietzsche. The famous Basquiat post paired the Sugar Ray Robinson painting, which seems to express a sense of isolation and embattlement, with the lyrics of Simon & Garfunkel’s “The Boxer,” a song that addresses similar emotions. “Basquiat identified with the struggling black boxer,” Gorvy wrote in his post. “Here he depicts middleweight champion Sugar Ray Robinson…, a powerhouse of muscle in his splendid orange boxer shorts.” Gorvy, who has about 97,000 followers, says he gets a sense of connection from Instagram, something missing in today’s global art world, with dealers constantly hustling and on the road.

Instagram made him realize, he says, that “there are a lot of people out there who like to be inspired, who actually wake up in the morning and like reading a poem or something beautiful. Almost every day someone is thanking me for doing this. And it’s opened a world to me of other people doing the same thing.”

As for Mike Krieger, Instagram’s sale to Facebook has allowed him and his wife, Kaitlyn, to become serious art collectors. Today much of what they collect is conceptual and process-based—sculpture by Adrián Villar Rojas and Ricky Swallow; photography by Wolfgang Tillmans; and work that blurs the lines between the two by Sara VanDerBeek, Pierre Huyghe and Thomas Demand.

Sometimes they see a piece or a show on Instagram and decide to check it out. But, Krieger says, “we’ve never bought a piece off of Instagram. I love seeing things in person.” Original story from www.wsj.com